29th May – 12th June

This project will take place at Cell Project Space in Bethnal Green and at The Old Operating Theatre in Southwark. A new video work by Jos Bitelli will occupy the exhibition space at Cell, with a series of events initiated by Rebecca Lewin will take place concurrently in the historic spaces of The Old Operating Theatre, with contributions from Sidsel Meineche Hansen, Nils Norman and others.

The title of this project, A Partition, is taken from Michel Serres’ seminal text The Parasite. In it, Serres proposes the parasite as a metaphor for human interaction. Rather than an insidious entity, Serres reappraises it as important due to its ability to profoundly affect the behaviours of the people and places surrounding it. Considered as such, the parasite is a key agent in social and economic relations and a crucial catalyst in their evolution. The notion of an individual becoming a partition - that is to say, something separate from these systems - is suggested by Serres as a form of protest.

The two locations of this project have been chosen as contrasting forms of institution, sites that respond to the relationship between the individual and the collective, or social, body. The possibility of the artist becoming a partition - a focal point that reveals and unpicks the transactional exchanges that surround their practice - will be explored both in the form of an exhibition and in events accompanying it.

Bitelli’s new video work All Doors and No Exits (2016) presents a combination of scripted and improvised actions performed by a group of healthcare professionals. As each set of verbal and physical actions is learned and performed, it also begins to disintegrate, drawing attention to the performance of learned knowledge prescribed and proscribed by systems of care. Revealing the mechanism of its own production, the film proposes a displacement of authorship that acknowledges the institution without demanding to be located within or without its structures.

In response to the idea of the parasite as a metaphor for human interaction, Hansen has invited Nils Norman to discuss two group-based projects: Norman’s Parasite (1997-8), which was a self-organised activity that piggybacked specific art institutional infrastructures in exchange for content provision; and the group-based piece CULTURAL CAPITAL COOPERATIVE OBJECT #1 (2016), which is part of Hansen’s show at Gasworks until 29 May.

Jos Bitelli recently presented a new performance for The Chisenhale Gallery’s 21st Century programme in February this year. Solo projects include ‘LimescaleTea' at tank.tv, London; 'To Gaze at Ten Suns Shining’ (with Sarah Abu Abdallah) at POOL, Hamburg (both 2015). Recent group shows include 'CO-WORKERS – Network as Artist', Musée d'Art moderne de la Ville de Paris; Pavillon de l’esprit nouveau, Swiss Institute, New York (both 2015); Place of Dead Roads, screening with Felix Melia at Centre D’Art Contemporain, Geneva; '89plus marathon', Serpentine Galleries, London (2013).

Rebecca Lewin is exhibitions curator at Serpentine Galleries, London.

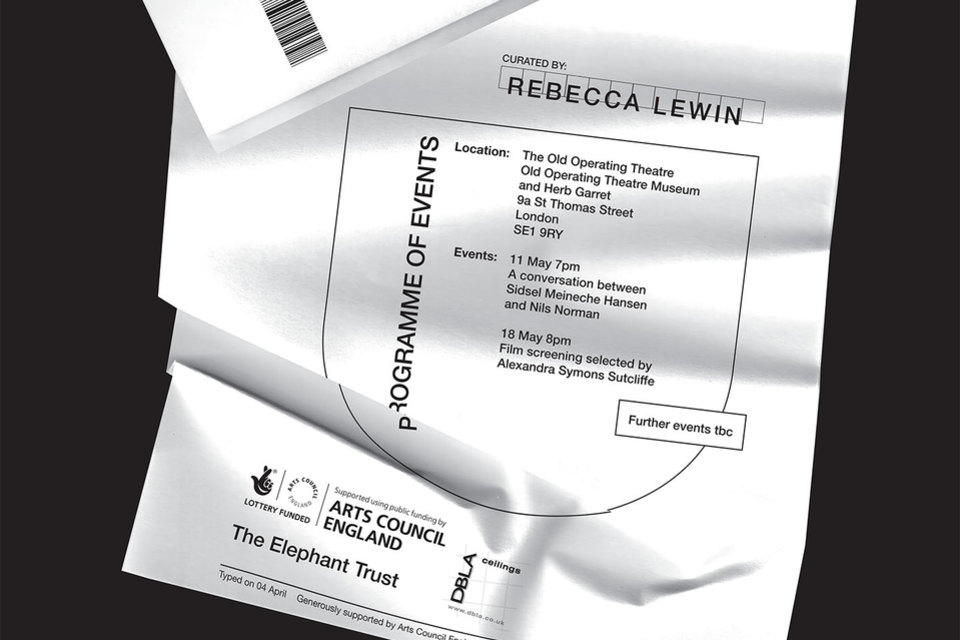

Event location:

11th May, 7pm

A conversation between Sidsel Meineche Hansen and Nils Norman

18th May, 8pm

Film screening selected by Alexandra Symons Sutcliffe

Exhibition Text by Rebecca Lewin

Contingent structures: All Doors and No Exits

This exhibition comprises a single video work set within an adapted version of Cell Project Space. Jos Bitelli’s two-channel video, titled All Doors and No Exits (2016), uses both screens at once, or switches between the top and bottom screen, or occasionally layers images one on top of another, giving the effect of multiple simultaneous viewpoints and repeated ‘takes’ of a series of rehearsals for a future performance.

The four actors are amateurs, and the work is contingent upon their specialised knowledge as healthcare professionals, as well as on their willingness to collaborate on its structure and filming. This reliance on the complicity of the actors and crew results in moments of self-organisation that recall William Greaves’ meta-documentary Symbiopsychotaxiplasm -Take One (1968). Written and directed by Greaves, who also appears in it as himself, albeit himself playing the role of director, it tests the construction of a film in all of its constituent parts by everyone involved, from a minute examination of the script to a debate about the meaning of the film. Three different film crews were hired; one to film the purported subject matter, the next to film the first crew, and the third to film everything. During one conversation held between - and filmed by - the whole group, one individual notes ‘Here’s a director that sets up a situation, brings [in] a crew of people who can think, and doesn’t tell them what’s going to happen… Let’s just take that for what it is and say that it leads to our participation in it.’[1]

The flatness of hierarchy that Bitelli proposes in the production of All Doors and No Exits is, however, unstable: in one moment, the voice of one of the actors is heard discussing the problems of getting a good take; at others, Bitelli’s voice as the scriptwriter or director is either heard off-camera, implied by the use of instructions passed to the actors via headphones, or apparently written out in subtitles. In this way, two hierarchies are addressed: that of filmmaking as a way of describing the body, and that of the way in which the body is circumscribed by medical language. In a lecture delivered at MIT in 2014, Yvonne Rainer remarked that ‘If narrative structure is an analogue for social hierarchy… then the disruption or messing around with narrative coherence has a positive function in pointing toward possibilities for a morefluid and open organisation of social relations.’[2] Rainer’s project is also applied by Bitelli to the possibilities and problems of an interchangeable relationship between doctor and patient.

The stark contrast between the clinical phraseology of the mental state examination that forms the basis of the work’s script and an emotive exchange between the actors that occurs halfway through the video, points to the importance of confronting the discrepancies in descriptions, classifications and experiences of the body as we have come to accept it today. The medical historian Barbara Duden has noted, ‘It was only toward the end of the eighteenth century that the modern body was created as the effect and object of medical examination. It was newly created as an object that could be abused, transformed, and subjugated. According to Foucault, this passivity of the object was the result of the ritual of clinical examination.’[3]

Understanding the patient (or client, in more recent terminology) as having been created by the language of the doctor (or service provider) and which also determines their treatment is therefore a relatively recent development. It challenges the 19th and 20th century’s increasing emphasis on the ‘natural’ body - one that is healthy, free from disease, and which all individuals are duty-bound to strive for as part of their subscription to a ‘body politic’. Lisa Blackman’s book The Body: The Key Concepts demands a reevaluation of this precept. She asks: ‘If the body is not simply a natural body, the rightful province of the life and biological sciences, then how can bodies be examined and interrogated through frameworks that have been understood as more social or cultural?’[4]The danger of understanding the clinical relationship as a quantifiable transaction (to follow the language of the client/provider principle) is perhaps just as real as perceiving the body as a quantifiable object.

The installation at Cell provides a setting within which to contemplate the separation of bodies and knowledge, and the hierarchies that result from this. Each of the key components - the false ceiling, the antibacterial hospital curtain, the white LED light panels - affect qualities of permanence and inviolability that are simultaneously revealed to be specious at best. The ceiling conceals all but one of the speakers that transmit the video’s soundtrack but allows sound to pass through it; the curtain partitions the space but can be moved at will; the lights only illuminate the half of the gallery that exists beyond the curtain. This is an approximation of rooms - offices, hospitals, airports, reception areas - that are associated with discomfort, boredom or apprehension. Normally ubiquitous to the point of invisibility, these elements recall other experiences in other spaces, institutional structures of work and health that we rely on but from which we are rarely given an exit. To refer back to Michel Serres’ text The Parasite, which inspired the title of the exhibition, the disruption of existing structures by revealing their contingent properties may be the most effective way to protest their shortcomings.

[1]William Greaves, Symbiopsychotaxipliasm - Take One (1968), 1hr 15min. Quote at 25min 37sec.

[2]Yvonne Rainer, ‘Where's the Passion? Where's the Politics?’, lecture delivered at MIT, Cambridge, Massachusetts, April 7, 2014.

[3]Barbara Duden, The Woman beneath the Skin (Harvard University Press, 1991), p.3.

[4]Lisa Blackman, The Body: The Key Concepts (Berg, 1998), p.10.

The Elephant Trust