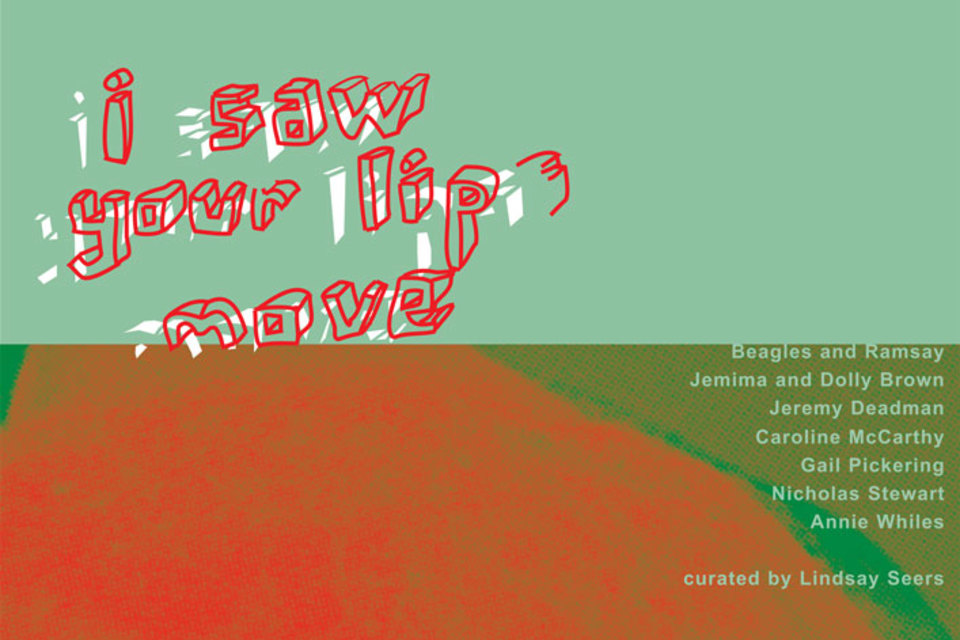

I Saw Your Lips Move

Jemima and Dolly Brown | Jeremy Deadman | Caroline McCarthy | Gail Pickering | Nicholas Stewart | Annie Whiles

Curated by Lindsay Sears

Some lifeless objects are invested with a kind of anthropomorphism, like those weeping Madonna statues and ventriloquist dummies. Of these two, one is a (possible) supernatural truth and the other is an absolutely apparent artifice. There's no doubt where the hand of the ventriloquist is, whereas, if the origins of the tears of blood (or milk) running down Mary's face were evident (squeezy bottle and a long tube), that whole moment would utterly fall apart.

The artists in this show are all ventriloquists rather than priests. They are willing to lay bare signs of artifice in their work; in fact, it's about the line between apparent artifice and belief. Jeremy Deadman, (like a true ventriloquist) throws his voice into his work. His tentative (in spirit) vocal impressions, issue from a commandeered object; as in 'Flayed', which consists of a wall-mounted clock that cries out in pain at each stroke of the hand. With Jemima and Dolly Brown the transference of life into dummies and toys seems frighteningly total and, as when the ventriloquist no longer knows who is controlling who, one wonders how much Jemima, and indeed Dolly, believes that the dummies live. In 'Work, Play, Bed All Day' (video) Dolly and Joe lie in bed serenaded by a singing monkey; none of them seem to want to do anything (maybe, actually, it's because they can't). Beagle's and Ramsay's knitted 'Budget Range Sex Dolls (Double Self Portrait)' have less trouble fully realising their inadequacies; slumping, without much sex appeal, in their pink woolly skin. These are more like Lamb Chop in the ventriloquist stakes; no one thinks Shari Lewis's hand is really a sheep, but still, it's weirdly alive with bathos.

Annie Whiles' works 'John of Lunchtime' and 'June in July' are densely sewn emblems whose contents are like those cryptic medieval icon paintings; where things are happening but none of it makes sense to us now. Her work might seem closer to the Madonna weeping blood but for the fact these images were always non-sequiturs from domestic fantasies; they put us in a position where we can believe in their odd propositions but not with a blind faith.

Nicholas Stewart's photograph 'Pastel Gothic' is an evident construct that has a playful fait accompli, whereby no matter how much it reveals itself, it still bemuses us as to what we are actually looking at - a burlesque pathway into blackness or a photograph of flimsy card. It implies a trompe-l'oeil - but perhaps that is the trick. In Caroline McCarthy's video work 'Making Something Beautiful' the artist is playing, with some conviction, Beethoven's Sonata no.14. The piano is out of sight - as actually, there wasn't one. If you watch her for a while you can, see the slight of hand -like the quiver of the ventriloquist's Adam's apple. Gail Pickering in 'Shapeshifter (hardcore)' sets up a scene with a conviction that also asks you to believe in it. In spite of everything, like with Brecht, something transformative happens that is unexpected; given the circumstances. Drawing on the symbiotic relationship of 'fat people and feeders' the control and transference to another, relates to a psychoanalytic model enacted in ventriloquism but brought to more extreme ends in this perverse real life fantasy.